The Lawrence, Kansas, tornado of 1981. Visible from over 30 miles away, as this photo, taken from Olathe, attests.

It’s a bit of a cliché to tell people you were in a tornado while growing up in Kansas. They almost expect you to say it. They think Kansans have tornadoes regularly for breakfast with their morning cups of coffee or perhaps ride one to work each day instead of taking the bus. It ranks right up there with being asked if Dorothy is your next-door neighbor or if you own a dog named Toto.

The truth is, while weather conditions have grown increasingly volatile over the past couple of decades, it was not all that common at the time—at least not when I was growing up. The city of Lawrence in the northeastern corner of the state hadn’t had an actual tornado tear through its populated streets for seventy years. Not since April of 1911. A very damaging storm, too.

CLICK HERE to read about the Lawrence tornado of 1911.

My grandmother experienced that one firsthand with her family. The Atkinsons were living in a beautiful stone house on the corner of Seventh and Louisiana in Old West Lawrence. And Mary Atkinson, or “Meema” as I called her when I was growing up, could vividly recall when the roof was ripped right off of their house. She was fifteen years old at the time, clutching onto the wooden banister as she made her way down the interior staircase to take cover, when suddenly, a huge pile of bricks—that only seconds earlier had been an exterior chimney—fell with an enormous crash right in front of her. She escaped death by mere inches. The family then took cover outside in the storm cellar, located in back, next to the house. Yes, just like the one in the 1939 MGM film The Wizard of Oz.

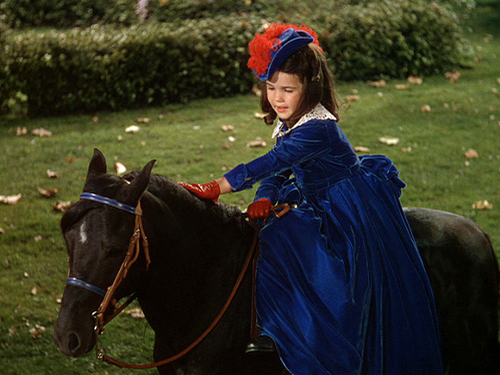

My grandmother, Mary Atkinson (“Meema”), approximately ten years old (1905). And their stone house, on Seventh and Louisiana, in a fairly recent shot.

When I was a child and first became familiar with the movie and the L. Frank Baum classic fairy tale, I used to ask Meema to tell me “the tornado story” over and over again. I couldn’t get enough of it. Instead of escaping death by inches, I pictured her coming ever so close to being whisked away to the Land of Oz. Hers was not a fortunate escape so much as a missed opportunity. At least that’s how I saw it.

Tornadoes were glamorous and mysterious. A potential magic carpet ride to incredible, distant worlds. Then I lived through one myself. And “glamour” isn’t exactly the first word that comes to mind anymore.

Wreckage from the Lawrence, Kansas, tornado of 1981.

It was early summer of 1981—June 19th, to be exact. Seventy years since Meema’s harrowing encounter with Mother Nature. And I had just graduated from high school. I was very active in the choral music department back then. Not long before graduating, I learned there would be a first-time-ever, summer edition of the wildly popular, end-of-year revue called “Showtime.” A handful of alumni—past, present, and future—were invited to be in it, and I was one of them.

On the evening of June 19th, we were gathered downtown at the Plymouth Congregational Church on Vermont Street for a rehearsal. It was a particularly warm and muggy evening. Everyone was talking about the weather: two dozen performers; Mrs. Jan Hutchison, our accompanist; and Mr. Lewis Tilford, the Lawrence High School choir director in charge of the show.

Sometime after seven that evening, Mr. Tilford called for a much-needed, half-hour break. My friend Mike decided he was way too hot and sweaty in his long jeans and wanted to drive home to make a fast change into a more comfortable pair of shorts. He asked me if I’d like to tag along for the ride. He also mentioned an ice-cold pitcher of lemonade waiting for us in the fridge. That was all I needed to hear to say yes. Little did we know, we were about to take the ride of our lives.

Lawrence has grown quite a bit over the past twenty-eight years, with a big expansion of suburban sprawl to the west. But you could pretty much cross the entire city by car in five minutes back then. So Mike and I jumped into his parents’ late-1970s, white, Pontiac Bonneville and headed for the southwest side of town.

Right away we noticed it was really weird outside. Everything was an intense, grayish-green color. Thick clouds were hanging over our heads like a stifling blanket. This phenomenon wasn’t all that extraordinary, though. Locals regularly referred to it as “tornado weather,” but as far as we knew, the city wasn’t even under a tornado watch that evening, let alone a tornado warning. We only heard, later on, that these menacing clouds had formed over the city in a matter of minutes. As Mike turned the corner west from Iowa Street onto 23rd, I glanced out of my side passenger window and gasped. There was an enormous whirlpool of a cloud directly above the open grassy field next to the car. It was slowly circling high in the air at an extreme, almost vertical angle. I’d never seen anything like it. I told Mike, who couldn’t see this phenomenon from his vantage point, that it looked like a tilted Ferris Wheel rotating in the sky.

Then we actually started joking about tornadoes.

“Auntie Em! Auntie Em!” I said, laughing at my own feeble attempt at levity, but we were growing increasingly concerned, wondering why we hadn’t heard the big sirens yet. “Shouldn’t they be going off now?” I added. We decided unanimously and rather naively that this obviously couldn’t be that serious of a situation.

Then the rain hit. And I mean hit. We watched a gray curtain of water advance toward the car and swallow us up as we turned left onto Lawrence Avenue. Mike slowed to a crawl, trying to see through the windshield. It was like driving through a car wash. By that point, we were just a few blocks from his house. A small red car pulled up behind us, and after we turned left onto 27th Street, its driver apparently grew impatient with our cautious maneuvering and scooted around us, taking the first right onto Mike’s street ahead. That’s when the hailstones began to fall. They lasted only a couple of seconds before the wind picked up. The rain and hail were suddenly blown sideways, and we could see much better again. Mike was inching his way home now, and we were maybe two or three houses from his driveway when the car began to shake. It was the most bizarre and frightening sensation, like a giant hand pushing down with great force on top of us while the car bounced off the ground, into the air. It felt as though we were being dribbled like a basketball.

“This is really bad!” I remember shouting, which was an understatement.

“I don’t think I can make it!” Mike shouted back.

Odd debris was flying across the street in front of us as Mike made one last attempt to pull into his driveway. A small outdoor grill went tumbling by. Pink insulation strips. Planks of wood. Several massive tree branches. A basketball and some lawn chairs. After he made it into his driveway, we sat in his car for maybe ten seconds longer at the most, terrified for our lives. The heavy Pontiac Bonneville sedan was still bouncing and rising off the ground.

“We should try to make a run for it!” I suggested.

“Not yet,” Mike replied.

I was scared to death and decided to ignore his advice. I opened the passenger door and heard the sound of cracking glass behind me. My ears popped, too, as if I’d suddenly come up too fast from a deep underwater swim. The wind was roaring now and whipping around me as I stepped out of the car, not even thinking about the consequences. I glanced across the front yard to the right of the house and saw a picnic table spinning by in the air. It was two houses down from us, less than a hundred feet from where I was standing. The large wooden table was being tossed around like a feather.

Things happened so fast that we didn’t have time to process everything in our minds. It was surreal. I remember thinking to myself, “There’s a tornado coming and we need to take cover.” It hadn’t occurred to me that we were actually in the middle of one right then. I’m not sure how we made it inside the house, but we did. I headed for the basement, but Mike went upstairs instead to check the windows. Although I had never put the theory into practice, we were always taught to open the windows of a house when a tornado was approaching, otherwise the roof might come off—or even worse, the extreme and sudden pressure changes could cause a house to explode.

Then I heard Mike hollering from upstairs. “Get up here, quick! Oh, my God!”

That’s when the tornado sirens sounded at long last.

I hesitated to join my friend but decided he must really need help, so I ignored the urge to take cover and bounded back up the stairs after him. I was still thinking the tornado was on its way. Instead, as it turned out, it had just left us.

“Where are you?” I asked apprehensively. “We should really go down to the basement, Mike!”

“In my parents bedroom! I don’t believe it!”

I rushed into the master suite upstairs and saw Mike staring out of the window on the side.

“Take a look!” he added as he pointed excitedly across the yard.

I joined him at the window and stood there in shock. I was gazing straight into the house next door. Inside of it. The exterior wall that should have been closest to us had been torn away. I was facing a life-sized doll’s house—a cross-section or cutaway, with most of the furniture and only three remaining walls. Mike’s neighbor was walking around inside of it. His expression was numb as he surveyed the enormous mess. This was his kitchen, or what was left of it. And I could see water shooting out from a broken pipe, concealed somewhere next to him.

The house next to Mike’s. The exterior wall and roof have been ripped away. The white Pontiac Bonneville is in the foreground, parked on the far side of Mike’s driveway. We were sitting inside this car when the tornado passed between the two houses. (Photo courtesy of Michael T. Sheridan.)

The wind had died down now. It was peaceful outside, and it had stopped raining. A gorgeous sunset was coming into view. It was cooler and clearer, and there was no humidity to speak of. Suddenly, this was an absolutely beautiful evening—in stark contrast to what had occurred less than two minutes earlier. That’s when we heard a distant car horn beeping repeatedly. I walked back to the dining room and saw something very strange, indeed. The sliding glass door leading out onto the back deck was wide open with its screen door closed and locked. We would later learn that this had saved the entire roof from tearing off the house. The dishes and knickknacks in the hutch by the dining table had been pulled from their cabinets and blown toward the open door, not away from it. This defied logic, at least in my mind, and demonstrated the power of such a dramatic pressure change. The objects had almost been vacuumed right out of the house.

Mike joined me in the dining room, then pointed up to the ceiling. We could see long, spiky nails sticking through, all around the house. The roof had been lifted up, perhaps as much as a few inches, then dropped back down, causing these nails to be displaced. They had pierced the plaster when the roof settled down again. These metal nails were everywhere around the perimeter of the ceiling, along the outer walls.

Then we heard the beeping car horn outside again and decided to have a look. We opened his front door and could barely believe our eyes. The house directly across the street from us looked like it had been broken in two. Its roof was gone, and we could see the small red car on its side in the front yard. A group of people were gathering around it.

The house across the street from Mike’s, taken from his porch. At the time of this photo, the small red car had already been rolled right-side up. (Photo courtesy of Michael T. Sheridan.)

The house to the right of it had vanished entirely. There was a narrow row of cement steps that led up to nowhere. It looked like an ancient, ceremonial altar from a forgotten civilization. Mike informed me that the owners were away on vacation. They left their house securely locked with all of its windows and doors closed tight. It had literally exploded from the sudden shift in pressure.

The house across the street from Mike’s and down one to the right. Completely gone except for the cement steps leading to nowhere. The edge of Mike’s Pontiac Bonneville, where we were sitting when all of this happened, is in the lower right foreground of this picture. (Photo courtesy of Michael T. Sheridan.)

We continued down the front steps to Mike’s driveway, and I noticed the rear windshield of the Pontiac had been cracked. I remembered hearing glass shatter when I opened my door to get out. Again, it was the fast pressure change.

We crossed the street toward the overturned car, and that’s when I realized what had happened. It made me cringe, and I had to look away. The driver who had been in such a hurry to pull around us had steered right into the path of the tornado. His small automobile was lifted from the ground with him inside it. He had apparently opened his door, attempting to escape in midair, and the automobile had landed on its side in the yard, directly onto his foot. His leg was now pinned underneath, between the grassy ground and the car. And he had been honking repeatedly for help.

Someone shouted, “Is there a doctor anywhere in the neighborhood?”, only to discover quickly that the man trapped in the car was a doctor himself.

Several men were standing next to the car on the lawn, gesturing for Mike and me to come over and help them. Their plan was to rock the car as gently as possible off of his foot, back into an upright position, but they decided they had enough people to accomplish this task already and instead asked us to call for an ambulance. These were the days before cell phones, so Mike and I had to run back inside his house first to see if the phone was still working. It wasn’t. Neither was anyone else’s in the neighborhood, as it turned out, with one astonishing exception: the guy with the kitchen wall torn off and all of that damage. The one right next door to Mike. His kitchen phone was working just fine. So we asked if we could come inside and call for help. After dialing for an ambulance, I asked if I could also call my parents to see if they were okay. I remember standing in the exposed kitchen, looking across at the side of Mike’s house, while I spoke to them.

Mom and Dad were unharmed, thankfully. In fact, they had just heard the emergency news bulletin on the radio about a funnel cloud touching down on the southwest side of town. They figured I was safe at the rehearsal a few miles away. I was supposed to be downtown in the Plymouth Congregational Church after all. That’s when I told them we had taken an unfortunately timed break and had driven right into the tornado.

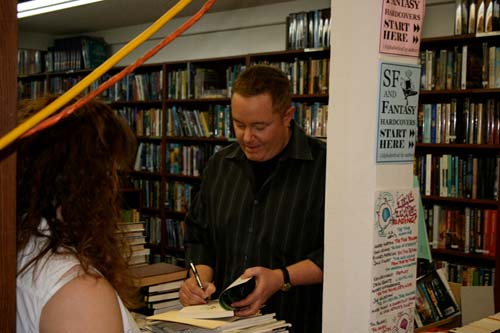

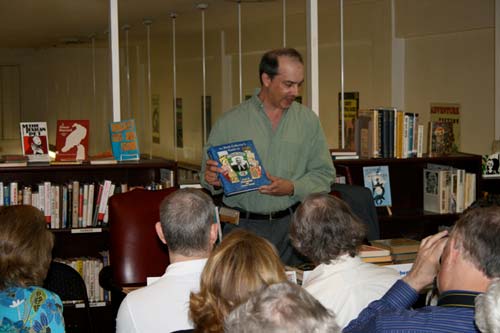

Within ten minutes, the ambulance had come and gone, taking the injured doctor to the hospital. Then Mike had the impulse to go back inside and grab his camera, and he snapped several incredible photos of the aftermath (seen here). Soon the national guard arrived in full uniform, driving their jeeps. They immediately closed off the neighborhood and informed us that if we left, we might not be able to get back for the night. They advised us to leave if at all possible. They were turning off all the utilities as a safety precaution and planned to comb the area for any downed power lines, broken gas mains, or ruptured water pipes. They would check IDs and limit return access to residents-only if anyone wanted to come back. Mike threw some of his belongings into an overnight bag, and we jumped into his Pontiac and drove away, heading for my house.

It took several days, weeks even, for me to process everything that happened to us that day. One thing was clear: we were extremely lucky. Freakishly lucky, if I may say so. Once all the analyzing had been completed by news reporters, expert meteorologists, friends, and local citizens, we learned that this F3 tornado had touched down less than a hundred yards from our car, right as we were attempting to pull into Mike’s driveway. It had basically landed on our heads. And the only reason we survived was that it didn’t have an opportunity to gather much steam. This tornado began its destructive path just behind Mike’s house. It had ripped off the side of the home next door as it moved past us in his driveway and obliterated the houses directly across the street. Several homes to the right of us were damaged, as well. But we had managed to escape without injury, sitting in Mike’s car, not more than thirty feet away from the tornado. Thirty feet.

Another house on the opposite side of Mike’s, across from his backyard. The damage surrounded us on every side, yet we remained miraculously unharmed in the middle of it. (Photo courtesy of Michael T. Sheridan.)

We also learned that the storm had in fact gathered plenty of steam, cutting through the southwest side of town. Sadly, thirty-three people were injured as it demolished more homes, businesses, a trailer park, and the local Kmart, where one young man was killed by falling debris.

CLICK HERE to read the Lawrence Journal-World Archive article about the tornado of 1981.

Twenty-eight years later, I still feel lucky. “I lived to tell the tale,” as they say. I thought I’d share this account with you—my own tornado story—just like my grandmother shared hers so often with me.

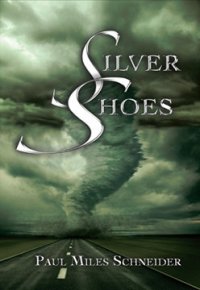

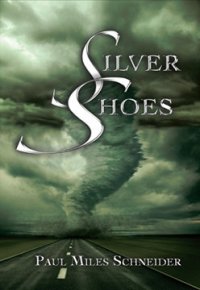

When I started to write the novel Silver Shoes, there were a few must-haves. I knew I wanted a tornado in it. Ultimately, I decided to use a fictional representation of the event on the cover.

The cover for SILVER SHOES.

My own cyclone is born out of an eerie blend of realism and fantasy, converging at a critical moment in the story. I did my level best to describe how it feels from a firsthand perspective, particularly the dramatic shift in pressure when my ears popped. It’s difficult to capture this sensation on film or TV—when a cold front meets a warm front and you’re trapped right in the middle of it.

Living through a Kansas tornado may be a cliché for many, but it’s also one of the unforgettable experiences in my life that led me to write this book.