Attack of the killer sequels!

You may not know this about me, but I’m someone who generally avoids seeing a movie with a number at the end of the title—even if I enjoyed the first installment. Actually, especially if I enjoyed it. I’ve been burned too many times and have grown leery of them. With few exceptions, I think most sequels are assembly-line products made for all the wrong reasons, and it shows. They also have this weird way of retroactively souring my impression of the first film and spoiling whatever made it special to begin with. You’re only as good as your most recent effort, so it seems.

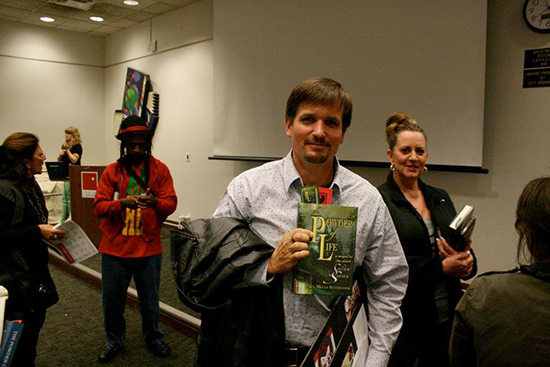

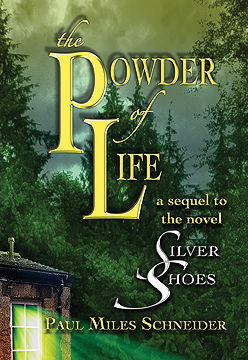

The “crooked magician” Doctor Pipt, as depicted by illustrator John R. Neill in L. Frank Baum’s “The Patchwork Girl of Oz.”

Let’s face it—a sequel is not an easy soup to make. Combining all the key ingredients in just the right way takes the creativity, planning, and skill of a master chef or, better yet … a wizard! So why bother to “concoct” one? Without a solid reason and a compelling premise, any effort on my part would likely result in disappointment. To say I’m skeptical would be an understatement. To say I’m flat-out against the idea would be closer to accurate.

And truthfully … I believe this is the best way to approach a successful sequel. Understand and acknowledge every reason on earth not to do it until you find the one really good reason to say yes.

My first novel “Silver Shoes” exists because I had a story in my head that just wouldn’t go away. After a solid year of internalizing every detail, reshaping, rehashing, and refining it, I finally had to fire up the laptop and tell it, simple as that. So the journey of discovery began for Donald Gardner and the Silver Shoes.

But a sequel?

There was no binding contract or burning incentive to carry on with it. The story had come to a satisfying conclusion in my eyes—at least that was my opinion after I finished its final pages.

I should say up front … proceed at your own risk!

SPOILERS AHEAD … or as the famous signpost in a classic MGM film once put it, ”I’d Turn Back If I Were You!”

During the better part of the first decade of this new century, I was a DVD and Blu-ray Disc graphics producer. Occasionally, I worked on behind-the-scenes documentaries, collaborating with a slew of talented “special feature” producers and studio clients. So to use a bit of shoptalk terminology from that world, this is my “making-of,” my “backstory,” my “behind-the-scenes featurette” exploring how it all came to be.

Now … press PLAY on your remote, and we’ll begin.

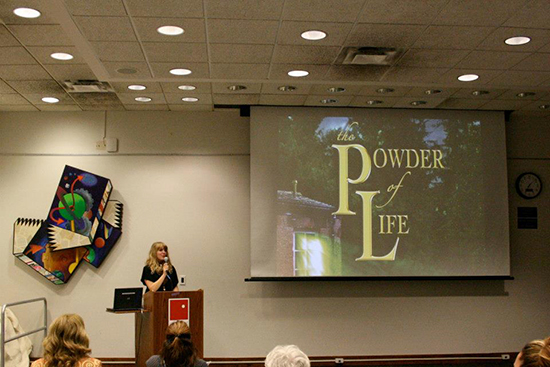

Since “The Powder of Life” is a sequel, I’ll start out by using an old broadcasting cliché: “You are joining this program already in progress.” I’ve posted before and given bookstore talks, interviews, and library presentations about how I came to write “Silver Shoes.” Still, with most serialized entertainment, they will give you an intro saying “previously on last week’s episode” before the new one begins. So I’ll do that now …

The idea for “Silver Shoes” came to me in a flash while I was staring at the other shoes. You know the ones I mean. They were worn by a talented up-and-comer named Judy Garland in 1939, and they were a different color.

An authentic pair of ruby slippers from MGM’s 1939 adaptation of “The Wizard of Oz.”

By pure coincidence, my good friend Barbara’s neighbor who lived in the same North Hollywood apartment complex with her owned a genuine pair of ruby slippers that were used in the film. One evening, we were invited over for a private viewing, and as I gazed at them up close and in person, I kept thinking, “These aren’t real.” They were designed by Gilbert Adrian and constructed by a studio wardrobe department.

Legendary costume designer Adrian.

Simple 1930s satin pumps with dark red sequins. Yet so many people are captivated by them, myself included. Some are willing to stand in line for hours just to get a quick look. The shoes have a magical aura about them, no question. An authentic pair can sell upwards of two million dollars today—a price that will likely climb even higher, in time. “But what if they were real?” I asked myself. “What if any one of us could put them on right now and they worked?” That would mean they had real magic powers … and once belonged to a real wicked witch … and that Oz was a real place after all.

That’s when the lightbulb went off above my head and the basic idea was born.

A quick side note: I must confess that there was always one aspect to the ending of “The Wizard of Oz” that bugged me: What happened to the shoes? We know that Dorothy clicked her heels together three times and was transported back to Kansas. The MGM film didn’t speculate further because her journey was a dream, and the shoes were merely part of her subconscious imagination. In the book, however, the trip to Oz actually takes place—and the shoes? They fall off while she is being whisked through the air and are lost forever in the desert.

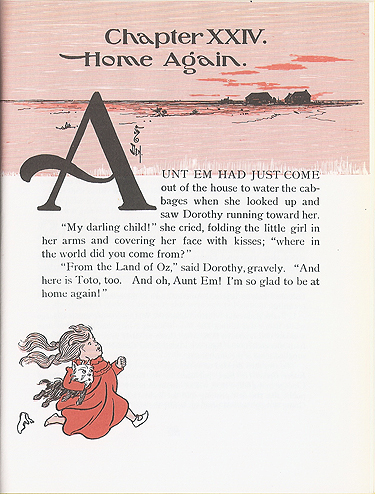

A page of L. Frank Baum’s “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” with W.W. Denslow’s illustration depicting the fate of the shoes.

So … putting the two ideas together, I had my premise. It would be about someone in our world today discovering these “lost” magic shoes and finding out that the story of “The Wizard of Oz “ is true—that it all really happened a hundred years ago.

After this idea hit me, I began to work backwards chronologically with it in my mind. Treating it as real, I would need to have convincing motivations for each event and character along the way. Early on, I realized that if the shoes were genuine, they wouldn’t be the famous Ruby Slippers from the 1939 movie, they would have been the Silver Shoes that L. Frank Baum first described in his story, forty years earlier.

Then why would Baum have written a children’s book about a young Kansas girl’s adventures in a make-believe land if, in fact, he knew the place existed and the story was true?

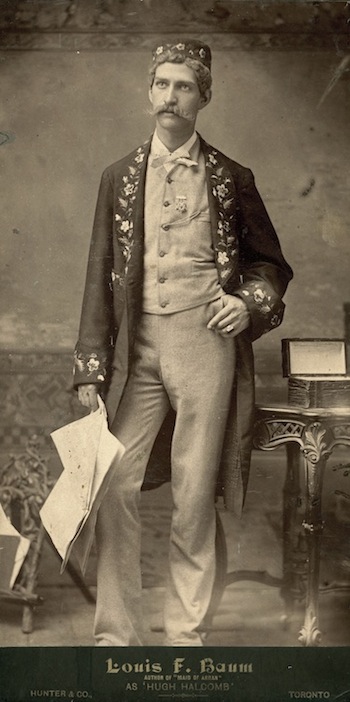

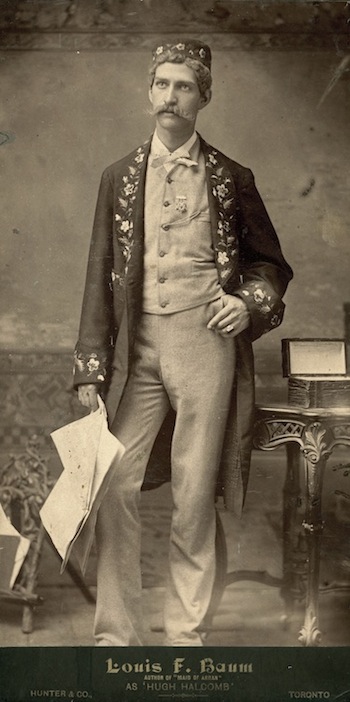

After doing some research, I decided to blend fact with fiction and create a plausible backstory that had Mr. Baum traveling throughout the Midwest as a china salesman, selling cups, saucers, and dinnerware shortly before the turn of the last century. That much is true. Lyman Frank Baum held many jobs before he became a famous author. Back in 1882, he even appeared as an actor in a touring play that he wrote himself, called “The Maid of Arran.” A stop on that tour was a just few blocks from where I currently live, in what is now Liberty Hall in Lawrence, Kansas.

L. Frank Baum, using the stage name of “Louis F. Baum,” in the role of Hugh Halcomb on tour in “The Maid of Arran.” 1882. (Photo courtesy of Jane Albright.)

I decided that for my fictional story, the occupation of a traveling china salesman was the perfect cover allowing him to scour the Midwest and investigate unexplained phenomena for the United States government. Baum would be an undercover agent in my novel, long before the FBI had been established, sent to investigate the remarkable disappearance of a little girl named Dorothy from Kansas, who had recently vanished into thin air during a tornado. By the time he arrived on the scene, she was home again, and after speaking with her, Baum realized she had been to Oz. This would imply that our government was well aware of its existence and was keeping the information hidden from the general public. But why? To what purpose? And why would Frank Baum expose such an incredible secret in a children’s book?

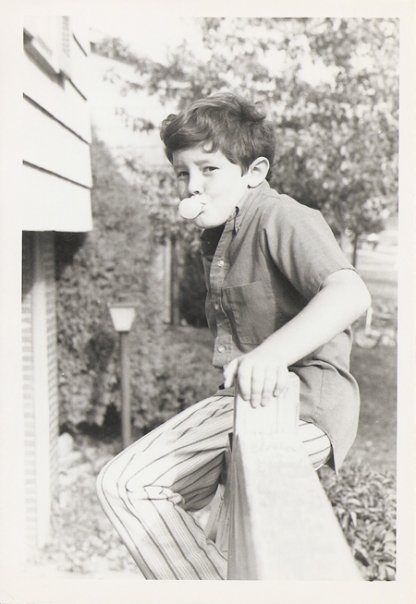

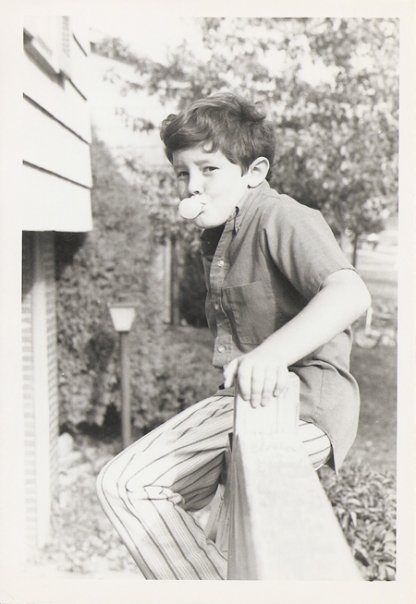

As the story continued to evolve in my mind, I created the protagonist Donald Gardner, an eleven-year-old Midwesterner who lives through this epic adventure with his family and friends in the modern world.

A photo of me when I was just about Donald’s age. I wouldn’t say Donald “is” me exactly, but there’s a lot of me in this character, no question.

I also began to realize that my experience as an interactive graphics producer was playing an unexpected role in its development. Part of my job working on home video releases was working with the content producers and coming up with the extra stuff—the fun quizzes and games. I would help develop concepts and scenarios, occasionally even writing them myself, with entertaining challenges for characters to overcome while inviting viewers to enjoy a thematic tie-in to the movie or TV show they had just watched. I’m not a gamer by nature or by hobby, but my mind was definitely in “game mode,” at least from a narrative perspective, while I worked on these interactive features and my adventure novel at the same time.

Once I started to write it all down, I finished an initial draft in about six months. Not too shabby for a first attempt, especially while working on “Star Wars,” the Harry Potter movies, “Men In Black,” “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” “Citizen Kane,” and dozens of other titles full-time during the day. But as I mentioned, I had most of the plot outlined in my head before I ever started.

Just some of the DVDs and Blu-ray Discs I had the pleasure and privilege to work on while I was a motion graphics producer in Los Angeles.

The next step, or so I thought, was finding a literary agent. I figured I would work toward having the book “traditionally published” while I moved on with a second draft, and since no larger publishing houses accept unsolicited manuscripts directly, I knew I needed an agent who would represent the work for me. It turns out I spent very little time on this phase—only about six weeks—before I made the decision to self-publish.

I did manage to send out a dozen “query letters” to specialized agents during that time, all of whom said on various websites that they were accepting author submissions. Right away, I heard back from several interested in reading more. That seemed like a good sign, so I forwarded my full manuscript to some, a chapter or two to others—whatever they requested. Then came the form-letter rejections, but also a couple of curious responses from agents who were surprised that this story was not for children. I never implied or claimed that it was. There is no inappropriate material in “Silver Shoes,” but the plot and language might be considered a bit sophisticated for younger readers. I’m sure an assumption was made on their part because “The Wizard of Oz” is a children’s book. Still, it was odd feedback, considering they were Young Adult or Adult-level Fantasy agents, not Children’s agents—and I had made it clear in my submission that the target audience was “Ages 12 and up.” And I really did mean the “and up” part.

It’s true, I didn’t simplify the language. Most of the characters are adults, and they speak like adults. There are also underground FBI agents, a secret society known as the Order of the Wizard, plus ideas and scenarios that are not easily digestible by children. It was suggested that I rewrite my story and make it directly for kids by paring down the plot and language significantly—even cutting the FBI out of it completely—or take it in the opposite direction and gear it for adults—meaning add more grit, violence, foul language, and perhaps a little sex along the way, all of which have sadly come to mean “adult” in today’s world.

I chose none of the above. The fact that these agents either didn’t understand, agree with, or like what I was doing, and instead tried to force this story into a typical, conventional publishing mold, led me to the conclusion that perhaps traditional publishing wouldn’t be the best choice for me.

The publishing world is changing rapidly. It was apparent in 2009 when I was preparing “Silver Shoes,” and it’s even more obvious to me today. A traditional publisher is no longer the sole road to success for a novel. Self-publishing—what was once known as “vanity press”—is now a viable, legitimate option and an increasingly acceptable way to tell a story and sell it to the public.

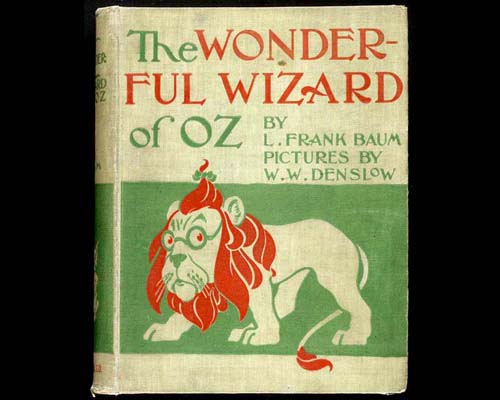

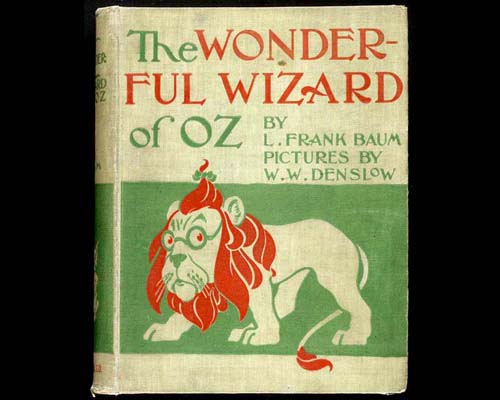

There was another reason self-publishing appealed to me, and it had to do with the history of L. Frank Baum and “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” His novel, as hard as it is to believe today, was a difficult “sell” to publishers. Baum endured a string of rejections claiming readers wouldn’t be interested in a modern American fairy tale. He found a publisher eventually who liked his story and believed in it, but also acknowledged that it was a risky venture.

It didn’t help that Baum had specific, nontraditional ideas about how he wanted his book presented. He asked for more illustrations and far more full-color plates than usual. He wanted a variety of colored inks to be used throughout the book as well, with color elements appearing on nearly all pages. In addition, he wanted his book sized smaller than normal vertically, making it almost square in shape for a child’s hands to manage with ease. His requests were uniformly rejected by the publisher who felt it would cost too much money and eat up profits. So Baum, in a bold move, offered to put up the financing himself for a first edition. He was willing to take the risk, because he believed in his vision. And while this isn’t exactly self-publishing, the sentiment behind it is the same. In the end, he got the book he wanted by paying for it out of his own pocket.

“The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” by L. Frank Baum. Pictures by W.W. Denslow. First Edition, 1900.

My choice to self-publish “Silver Shoes,” in a way, is a direct nod to L. Frank Baum, honoring his original creative journey with “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” Art imitating life, imitating art. He held fast to his vision, despite conventional wisdom and the advice of contemporary professionals.

I’m happy to tell you that “Silver Shoes” has been well received. Reviews are highly favorable overall, and sales have been solid, particularly for a first novel and a self-published book in today’s market. I was also surprised and pleased to learn that it had been selected as a Kansas Notable Book for 2010 by the Kansas Center for the Book and the State Library of Kansas. I received a nice shiny medal in a ceremony held at the state capitol. It was presented by the state librarian of Kansas. But even more rewarding, because my book had made the list, it was quickly purchased by public and school libraries across the state. Having this distinction created an instant awareness, and as they say—you can’t buy that kind of publicity! Soon I found myself invited to speak at libraries, book conventions, bookstores, and public schools. It was a marvelous, unexpected turn of events, and I’ve met many terrific people in this state and beyond who love books and reading—and Oz.

So … what about a sequel?

I had no intention of writing one, as I mentioned earlier. Would there be anything new for these characters to discover and learn? Was there something more I wanted to say about them as an author? Was there a way to turn my predisposed skepticism into optimism or even, dare I say it, enthusiasm?

When I first wrote the final two chapters of “Silver Shoes,” I decided to answer all questions that had been posed along the way and solve each mystery that Donald and the others had encountered. Everything was tied up in a neat and tidy bow, and as I read through it again myself … it was resoundingly dull. It felt forced, not unlike the final moments of a sitcom where all the problems are solved just before the end credits roll.

So I went back to work and rewrote those chapters. Now the storyline surrounding the shoes comes to a satisfying and dramatic conclusion as it should, but a few other mysteries are left up in the air. I wanted it to have more of a natural feeling and to leave readers with a sense of awe, but also an understanding that this was only the beginning for Donald and his friends. A brand new world of possibilities had just opened up for them.

I’m happy with this change, and I think it’s a much stronger conclusion, but it did invoke a fairly universal reaction from readers. The first comment I almost always heard was, “I want to know what happens next!”

I shouldn’t complain. It’s much better than, “Well, I’m glad that’s over with!”

In addition to my inherent desire to please readers, there was another strong incentive building—something I wasn’t expecting, and it was a far more serious and deeply personal motivation.

I faced a dark storm in my life right then. I could see it approaching on the horizon, just like a tornado making its way steadily toward me. But what I didn’t realize was how powerful it would be and how much it would change my life forever.

My mother Jo Anna March Clift around 1990. I surprised her when I took this candid photo while she read the newspaper at her cousins’ waterfront house on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

My mother had been ill for years with emphysema and dementia. She had endured a slow decline and fade from this world and from life. I did my best to help in every way possible and to work through my own stress and grief, as we all must do in situations like this when the time comes. Mom and I were extremely close, and it wasn’t easy. I decided that a positive way to calm my nerves and perhaps escape the inevitable just a bit, at least in my mind, was to start writing again. That’s when I considered advancing the story of Donald and his friends, picking everything up where it left off.

I decided I wanted to know what happened next, too.

More questions were being asked now. Several readers had written by this point and told me they wanted to know who the evil sorcerer was in the woods in Germany—the one who threatens Donald’s life and commands the flying monkeys to come get the shoes. They wanted to know who the mysterious woman was at the beginning of the book who sells Donald and his mother the antique silver shoe that kicks off the entire adventure. They also asked about the FBI’s top-secret facility where they routinely explore the most extraordinary classified cases, not exclusively related to Oz. Donald and the others had been invited to take a grand tour. And finally, a question that I was asked frequently: would Donald ever travel to Oz himself and get to see firsthand what it was like?

By the time “Silver Shoes” was published in March of 2009, I was three chapters into the first draft for “The Powder of Life,” and my mother was now in a nursing home, nearing end of her life. I’m glad she got to see my first book published even if she wasn’t able to read any longer. She held it in her frail hands and showed it with pride to her nurses, saying, “That’s my son!”

Three months later, she was gone. I tried hard to prepare myself as much as possible, but it wasn’t any use. And I didn’t realize that the storm was far from over. In fact, it was just beginning. Six weeks after my mother passed, my father, whom I was equally close to, was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer. Four and a half months later, just shy of six months to the day after Mom’s passing, my father died as well.

My dad Leonard Schneider and me looking at a robin’s egg in our backyard in Lawrence, Kansas, around 1972.

So I published my first book and lost both my parents, all in 2009.

That’s when I stopped writing. I stopped working and stopped dreaming, too. Months went by before I was able to focus again, harness my imagination, and begin to see the future. I started, slowly but surely, to work through my grief by writing. Suddenly, I had plenty to say as an author and plenty to say about these characters.

It dawned on me, at this point, that I was writing a novel called “The Powder of Life,” which is the name of a mysterious, magic substance from the Land of Oz that gives life to nonliving objects and prolongs it for the living—precisely at the moment I was mourning a monumental loss of life around me.

I’m sure you can understand that the notion of life itself, its immeasurable value, the prospect of controlling or sustaining it, the possibility of losing someone you deeply love, trying to connect to the memories you have and hang onto them as long as possible—all played into this new book.

“The Powder of Life” is without question an action-adventure story, above all else, just like “Silver Shoes.” There are twists and turns, battles, mysteries, surprises, and even a few good scares along the way. But the influence of life and how it’s perceived by others is a critical facet as well.

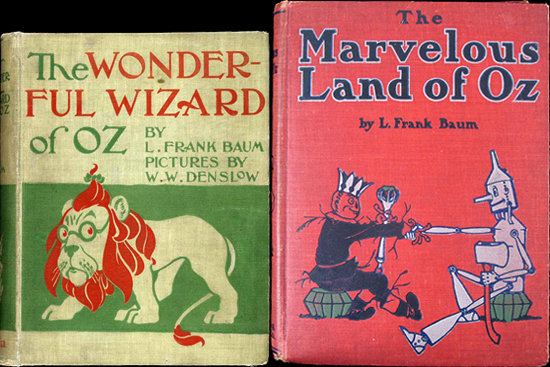

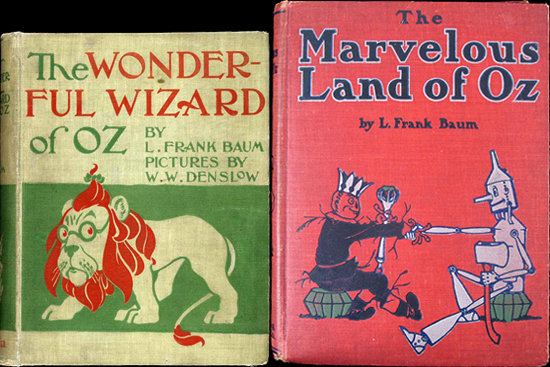

Initially, I chose the magic powder as a catalyst because I wanted to draw a parallel with Baum’s own sequel to “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” called “The Marvelous Land of Oz.” Just as the Silver Shoes are introduced in his first book and play a key role at the end by helping Dorothy get back home, the powder is introduced in his second novel and helps his characters achieve their goals as well.

First edition covers of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” (1900) and “The Marvelous Land of Oz” (1904) by L. Frank Baum.

I’ve drawn other parallels between Baum’s first two Oz books and my own first two adventures—little intentional nods along the way, starting with the main characters of both stories. It’s no coincidence that Dorothy Gale and Donald Gardner share the same initials, in fact, the same first two letters of both names.

But I will stop short of revealing more now. Hopefully, part of the fun in reading these stories is not only finding out what happens next, but discovering the subtle parallels and making these connections yourself along the way. It isn’t remotely essential that you read any of Baum’s Oz books prior to mine. My protagonist Donald Gardner hasn’t read them either. Still, it will enhance your experience if you have. And perhaps even after reading my novels, you might enjoy discovering the source for these adventures and the primary inspiration for writing them.

One last thing I’d like to discuss—and it’s a question I’ve often posed: what makes the story of “The Wizard of Oz” so special to me?

In a way, I think I’m living it. I grew up in Kansas and longed for incredible adventures in other lands. I wanted to get out into the world and search for happiness. In the end, I realized that what I was looking for, the contentment and peace I was seeking, could only come from within. I wasn’t going to find them in a place or a person or a thing.

There is definitely a “fantasy” element to this story, though—and I don’t mean the part about traveling to Oz. Many of us have been to unimaginable places or have lived through astonishing situations that we never dreamed were possible. I equate this to “visiting Oz” in my own life. The real fantasy of the story, however, is that after Dorothy has been through her extraordinary experiences, she gets to go home—back to the way things were. In reality, none of us truly get to go home again. The world has changed, and our experiences have changed us forever.

I moved to Lawrence, Kansas, in June of 2010, about six months after my father died. I tell people that I moved “to Lawrence,” not “back to Lawrence,” and there’s a difference. It’s not a retroactive development, because it can’t be. The world where I grew up—the Kansas of my youth—doesn’t exist anymore. We’ve both moved on. We’re not the same anymore.

I think that’s why the ending of “The Wizard of Oz” resonates emotionally for me: Dorothy gets to go home.

I first heard Hamilton Meserve discuss this when I met him in 2010. He is Margaret Hamilton’s only son, and Margaret (for those of you who don’t already know) played the Wicked Witch of the West in the classic MGM film of “The Wizard of Oz.” Her son’s words struck a chord back then and have stayed with me to this day.

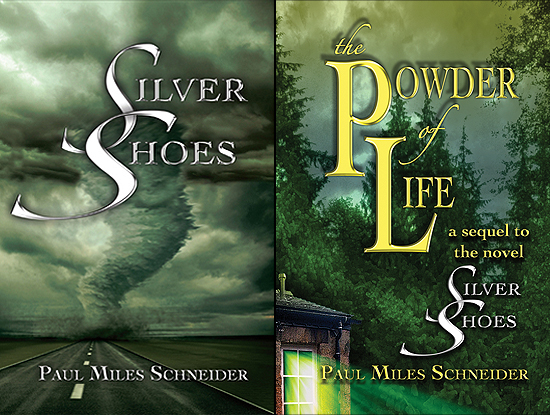

First edition covers of “Silver Shoes” (2009) and “The Powder of Life” (2012) by Paul Miles Schneider.

So many things have inspired and influenced me to write “Silver Shoes” and its sequel “The Powder of Life.” Some are real and some imagined. Some are events from my own life and some from other people’s lives. Hopefully, as you read the stories, you will be inspired and influenced as well.